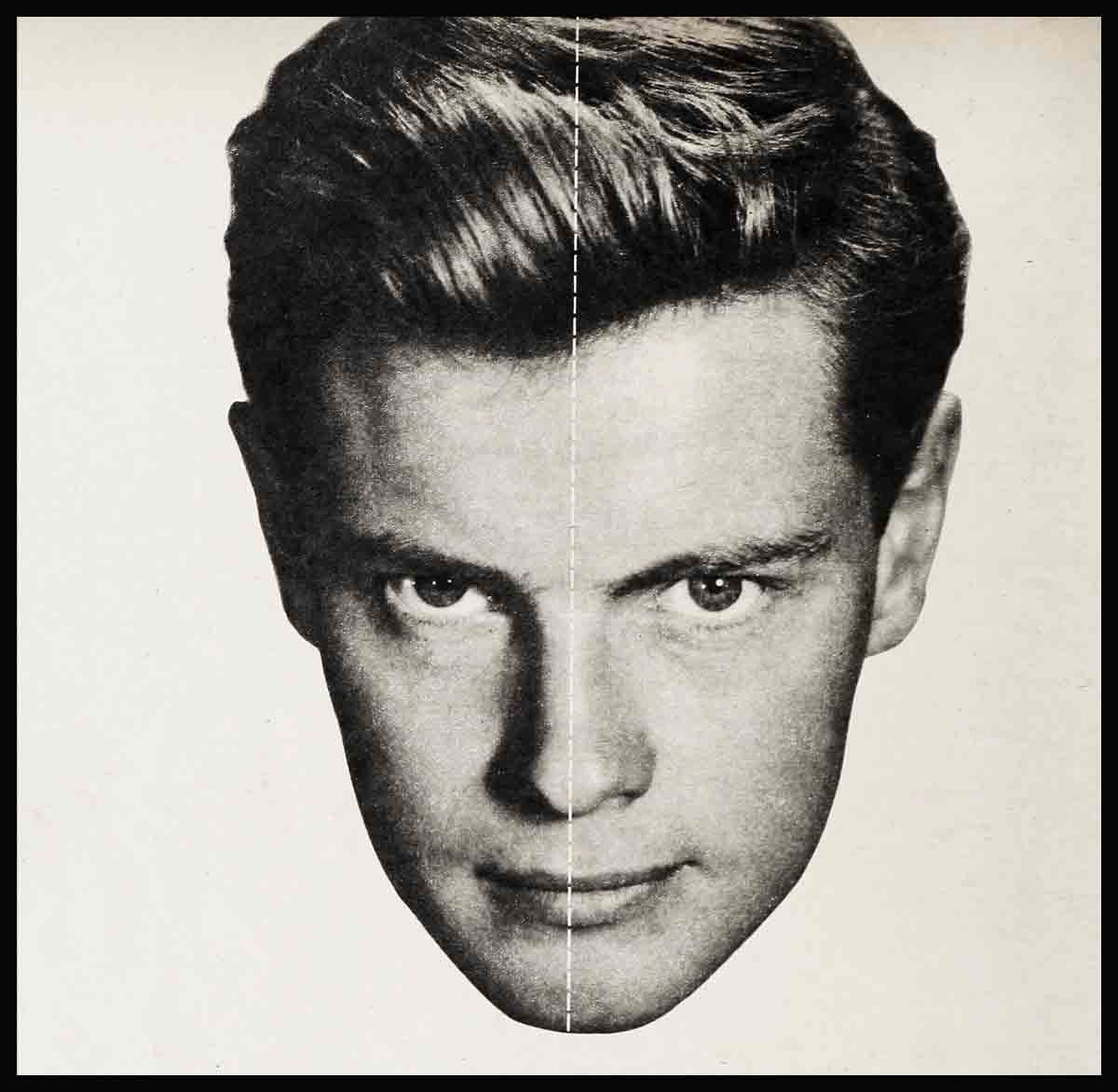

The Two Faces Of Troy Donahue

“Troy Donahue,” said Sandra Dee’s mother, “is one of the nicest, best behaved boys in Hollywood. I have complete trust in him. There are few boys I’d rather see take Sandra out than Troy.”

“Every time I hear what a nice guy Troy is supposed to be, it makes me burst out laughing,” said a former girlfriend of his. “And it’s not just because of what happened to me. Since we broke up, he’s been going with Nan Morris for two years. And what happened? When she caught him making love to another girl in his apartment—while they were still going steady for two years—and demanded an explanation, he threw her out bodily—!”

Could this be one and the same Troy Donahue?

It is!

But how could a fellow like Troy have such a wonderful reputation with some people, and create such a strong antipathy with others? Why has it never been brought to the surface before? And what turned him into the kind of guy he is—which is a far cry from the typical young Hollywood leading man type of the Tab Hunter, Rock Hudson, Edd Byrnes tradition?

Those who know him closely agree that there is in Troy a temper, a fire, a drive, an ambition that seems in direct contrast to the easy-going, pleasing mannerisms that has endeared him to Hollywood mothers and daughters alike.

Much of the answer to Troy’s twin behavior can be found in his own background.

Troy’s father was the head of General Motors’ motion picture division. His mother was a stage actress, who retired after her marriage. The Johnsons—Troy’s real name was Merle Johnson, Jr. until agent Henry Willson changed it to Troy Donahue—had a fashionable home in Long Island, and an equally fashionable apartment on New York’s East Side.

Troy himself attended some of the best schools in the country, including the New York Military Academy at Cornwall-on-the-Hudson in upstate New York. And if it hadn’t been for a severe knee injury he suffered during a track meet in his senior year, he would have continued to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Undoubtedly he had all the advantages of a rich man’s son.

And this is where his trouble started.

He remembers being sent to first grade in flannel slacks, jacket, white shirt and imported tie, and expensive custom-made moccasins which were in dire contrast to the dungarees and tee shirts worn by the other boys. Right away they treated him like Little Lord Fauntleroy.

During the very first recess, Troy found himself at the bottom of the heap of six boys who were beating up on him, and tearing his clothes to shreds. Yet when he came home he would not tell his parents what happened, and why. But thereafter, he tried to assimilate in his own way. On the way to school he would mess up his clothes by rolling in the dirt, by tearing his shirt, by ripping off buttons.

In wanting to look like the other boys, however, he went overboard to such an extent that the teacher finally sent a note to his parents, demanding to know why they sent him to school looking like a little tramp. As a result, he got it from the other side too. They could not understand how a boy like Troy, raised by a governess, could feel so indifferent about his own appearance!

Troy’s attempts to be like others continued to get him in trouble.

He was twelve when he snitched his father’s double-barrelled shotgun out of the glass-enclosed cabinet in the den, and sneaked out of the house to meet a pal, with whom he went on a hunting expedition.

They stalked through the swampy area near the Johnsons’ Long Island home, but the only thing they could find were some crows. It was good enough for them. Troy fired two shots in quick succession before he reloaded and handed the gun to his friend, who managed to get off just one more shot before they heard someone call out.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if this were a cop?” Troy giggled.

“Sure would be,” his friend agreed.

It was! A few seconds later they were whisked to the nearest station, and booked on six counts—hunting out of season, hunting without a license, hunting in a residential area, trespassing, walking around with a loaded gun, and carrying a gun while being under age!

Needless to say, his father was not in a cheerful mood when he had to bail out his son.

It wasn’t long, however, till even the restraint of his father was gone. Merle Johnson died when Troy was barely fourteen. Yet if anything, Troy’s ambition to be accepted by the group, to be one of them, to be important in his own rights, grew with age.

At fourteen, except for his family’s wealth—which he tried to ignore—there were other things he felt he could boast about to raise his importance, such as the famous people he met at his house, and the trips he had taken. But instead of winning his fellow students’ respect, he earned their jealousies.

The situation changed for the better in the next couple of years, when Troy shot up to nearly his present six-foot three. Tall, well-built, and strong, he became a member of almost every athletic team in school, and was instrumental in winning victory after victory for it. And with it, the adulation and admiration of his fellow students.

Troy wanted more than just to prove himself on the football, baseball and basketball field. He wanted to be accepted so badly that he went to any length to achieve being a “regular” guy. This often ran counter to Mrs. Johnson’s wishes.

The relationship between Troy and his mother had become strained already during his father’s long illness. Looking back, he now recognizes the tremendous responsibility she took on when her husband became incapable of making decisions, and it was entirely up to her to raise Troy and his younger sister, Eve, who is now fifteen.

Yet Troy began to resent more and more what he considered his mother’s over-concern. He was afraid she would make a sissy out of him, by keeping him from doing what the other boys did. And so he rebelled—never realizing that the other boys’ parents were often just as opposed to their offsprings’ actions as she was.

For instance, after ball games the other boys would frequently sneak off to a little beer joint, strictly off-limits to them. When Troy’s mother heard about it, she promptly forbade her son to go along. He did anyway. When he was seen by a friend of the family, who told his mother, she bawled him out right in front of his classmates when he came home. This made him feel all the worse.

Thereafter he would often sneak out after his mother was asleep, usually through the bedroom window.

Troy got away with it till he attended a senior party one night, where everyone had a lot more to drink than was good for them. Troy himself drank so much that he felt ill, and seared. All he wanted was to get back to his house, and his bed. He never made it.

A friend drove him back to his place at three o’clock in the morning. As Troy was trying to raise himself up to the porch, he fell over the lawn furniture which, in turn, collapsed with a big bang. “I can still see my mother come running out of the house,” he remembers, “shouting that if I could stay out this late, I might as well stay out a little longer, and slammed the door in my face. I crawled back on the lawn and fell asleep. It was ten o’clock the next morning when I woke up—just in time to see people stop on their way to church. I’ll never forget those expressions as they saw me on the front lawn, still dressed in a tuxedo, obviously sleeping off a hangover—”

The unruliness, the rebellion continued. Troy was just about to get his driver’s license at sixteen, when he was out with a group of friends, one of whom let him drive his car. He got caught by the police for going through a red light. The offense, in itself, was not too serious. But when the officer found out he only had a student’s license and was not allowed to drive without an adult next to him, he promptly called Troy’s mother. Mrs. Johnson became so upset that although he was supposed to have gotten his license two days later—and a car with it—she told him he would have to wait a full year before she would allow him to get his own car.

Again her strictness had the opposite effect.

To show his independence, one night Troy sneaked out of the house and headed for the garage. With all the strength he could muster he rolled out the family car and drove off, to pick up a girlfriend.

As bad luck would have it, about an hour later his mother decided to visit some friends. She didn’t check Troy’s room to see if he was still there, asleep. When she realized her car had disappeared, she naturally presumed it was stolen, and notified the police. An all-car alert was promptly put out via police short wave, giving the license number and description of the ‘stolen’ car, a brand new Cadillac convertible.

A cop finally found it parked in front of a drugstore. “Who’s been driving the Cadillac?” he demanded in a loud voice when he walked in. Without hesitation, Troy—who was having a soda with his girl, and another couple—admitted it was he. To his humiliation the policeman handcuffed him, and dragged him to the nearest police station to book him for theft. Not till his mother was notified was the mystery cleared up, and Troy released.

Mrs. Johnson hoped that a military school would straighten out her boy. For a while it looked like she was right.

Troy rather enjoyed his life at the New York Military Academy at Cornwall-on-the-Hudson. He did so well—both academically and in sports—that he became a student officer. Yet even this couldn’t keep him out of trouble, indefinitely.

In his class was a Cuban boy, nicknamed Gato, the Cat. He was a tall, quiet, strange sort of boy who didn’t associate with others, and a fanatic about cleanliness and health. While other students would get out of bed at 5:40 in the morning, he got up at 4:30 to do calisthenics on the parade ground. He brushed his teeth ten times a day. To sneeze in his presence was a sin to him.

His behavior caused the other fellows to constantly play tricks on him, particularly since Gato was not considered too bright. One day, Troy remembered, one of the cadets told him that if he would stick his finger into a light socket, he would light up. He did. And got knocked out. It was a miracle he wasn’t killed!

Gato particularly didn’t like Troy because the two of them had been in competition for high jumping for some time, with Troy, the top athlete of the school, always outdoing him.

One day as the cadets were sitting around the high jumping pit, looking at all the earthworms crawling around in it, one of the boys got an idea. Why not take a handful of these worms and put them on Gato’s pillow?

Everyone thought it was a hilarious joke, but who would do it?

Troy volunteered. He picked up a handful of the earthworms and carried them to Gato’s pillow.

Three minutes later the dormitory door flew open, and Gato rushed out and across the parade grounds straight to the commandant’s office.

The commandant had a hard time containing himself, but had no choice but to promise the boy proper disciplinary action. During the final inspection of the day, Gato was permitted to step forward and ask his officer—Troy—for permission to speak up. “As all of you know, someone put worms on my pillow,” he shouted. “If whoever did it is not too much of a coward, I want him to admit it now.”

Troy took a step forward. Before he knew what had happened, Gato had hit him like a freight train. It took half a dozen men to pull them apart again, bloody and exhausted from the brief but violent encounter. The commandant promptly told them that if they wanted to fight, they should do it with gloves on, in the gym. They agreed.

In spite of the gloves’ cushioning effect, the result was probably the longest and most brutal fight in the history of the military academy, with Troy getting the better of Gato but, as he admits, not much better. Yet when it was over, Gato’s anger was satisfied. He was willing to shake hands, and eventually he and Troy became the best of friends.

Troy learned a very fundamental lesson that day. If anything has to be done, good or bad, it should be done promptly and openly, and not held back. If he hadn’t stepped forward that day, Gato’s suspicion might have grown to where they could never have made up.

By the time he came to Hollywood, Troy felt he had outgrown any tendency to be hurt. He soon found out differently. What’s more, when a crisis arose, he continued to resort to his fists to settle it.

Shortly after he arrived in California, he took a group of friends to Gogi’s, a coffee shop on the Sunset Strip. In contrast to a lot of other customers, Troy was extremely well dressed. Furthermore, he still had enough money left to pay the bill for the five of them—which caused a disgruntled beatnik at one of the tables to make a crack about the big, tall, New York show-off who was all dressed up like a Christmas tree.

Troy turned for an appropriate reply. Before he got very far, the beatnik stormed toward him.

Troy was tall and strong enough to have held the man at bay. But his temper blew up and with four well-laid punches, he was laid out flat.

Five minutes later he found himself in a police car, bound for headquarters. Only an influential friend’s influence managed to cover up the incident.

Yet behind this aggressiveness, there is another side to Troy, equally, if not more powerful—a sensitive, understanding maturity far beyond his years. And contradictory as it may sound, his early environment was responsible for this, too. Particularly the death of his father.

Till Troy was twelve years old, he could never remember a single day that his father was sick. In fact, he was probably the healthiest, most athletic type of man he ever knew. The first indication that something was wrong occurred the afternoon they playfully wrestled on the front lawn. To the surprise of both of them, Troy managed rather easily to pin his father on his back.

For days after, the older man began to feel weaker and weaker, till he went to the Columbia Medical Center in New York City, for a complete check-up.

Nothing could be found wrong at the time.

As the weeks went by, he grew weaker, without any apparent reason. A painful ripple developed in his muscles, which made it continually harder for him to move, till he finally decided to go to Johns Hopkins’ Hospital, near Baltimore, Maryland, for another check-up. This time the doctors quickly discovered the trouble—hopeless, acute sclerosis, which would paralyze him progressively until it would finally draw life out of him completely.

Only they didn’t tell him, because obviously he didn’t want to be told. And so they described it as a disease with similar symptoms, and hopes of complete recovery.

But someone had to be told the truth, and that’s how it came about that Mrs. Johnson and Troy were to share the awful burden till his death. For two years Troy lived with the knowledge that his father would die without anyone being able to do anything about it.

“At first I couldn’t believe it myself,” Troy remembers. “To make it worse I was plagued by a feeling of guilt whenever I visited him. I did things which weren’t right, yet mother never told him. On the contrary, she assured him how wonderfully behaved I was, which made me feel all the worse. Oh how I wished the things she told him about me were true—yet it seemed the more glowing terms she used, the stronger my reaction to do the opposite—the worse I felt about it. It was an uncontrollable, vicious circle.”

Every time Troy visited his father at the hospital, the old man was a little bit more paralyzed, to where finally he could only make known what he wanted with the help of a chart on the wall. Only six people—Troy included—would be able to point to one of the drawings, and according to the way Merle Johnson blinked his eye, knew what he wanted, whether it was to eat, to rest, to get a bath, whatever it was.

In spite of everyone’s attempts to keep the truth from him, Merle Johnson finally realized he was dying. But then he had but one day of life left in him.

Troy found this out when he visited his father that afternoon. Merle Johnson somehow managed to tell him to take his gold watch from the night-stand. “It was his most cherished possession,” Troy recalls with sadness in his voice. “When he gave it to me, I knew he’d lost hope. . . .”

Troy was sitting in an ice cream parlor with two friends the next day when the maid ran in breathlessly. “Come home right away!” she shrieked.

Troy looked at her with quiet composure, “Dad?”

She broke into tears. He knew the answer.

The other fellows were surprised that Troy didn’t seem shocked, or hurt. Quietly and dutifully he went home and then helped his mother make the necessary arrangements for the funeral and after.

“My immediate feeling was one of relief that Dad’s suffering was over. It took me months to find out what I had really lost when he passed away.”

Yet after his father’s death, instead of becoming more dependent on his mother, his own feeling of independence grew. Partly he was still afraid to become a mama’s boy if he couldn’t assert himself, partly he felt that he was now the man in the family who, in spite of his young age, should have a voice in determining at least his own future. And so, when it came to a most important choice—which career to pursue—he found himself opposed to his mother’s wishes.

Through her own career in showbusiness, as well as her husband’s position as head of the motion picture section for General Motors, Mrs. Johnson had been close enough to the entertainment business to be aware of the disappointments it could bring. She didn’t want Troy to face a life full of doubts and insecurities.

From riches to rags

On the other hand, once his knee injury prevented his appointment to West Point, Troy had made up his mind to become an actor anyway. He took up dramatics in school and when he still couldn’t get his mother’s support, after his graduation, he saw no choice but to walk out of the family home, almost penniless.

For almost two years he subsisted on whatever he could make as a messenger boy, construction laborer, waiter, counselor at boys camp and other odd jobs which enabled him to study acting under Ezra Stone and get further experience in summer stock. He lived in cold water walk-up flats, the YMCA. He often got along on one meal a day, determined to succeed without asking his mother for help. Once he was so broke that he had to walk seventy-six blocks to save a dime subway fare.

It was Darrell Brady, an old friend of his father’s who brought him to Hollywood by offering him a job with his commercial film company. It was another friend, actress Fran Bennett, who introduced Troy to her agent, Henry Willson, who in turn was responsible for getting Troy a test at Universal-International, which eventually led to the lead, opposite Sandra Dee in A Summer Place, and as a result of it, a starring part in The Crowded Sky.

Once Troy was on his way to becoming established—professionally, personally, and financially—his relationship to his family changed abruptly. Troy suddenly became so conscious of his responsibilities as head of the family, that he was determined to do something about it. He sent for his mother and younger sister. He found them a place to stay. When his mother needed financial assistance, when her income from her investments did not come in on time, he was always ready to assist. He now attends P.T.A. meetings for his sister, Eve, and has adopted other parental prerogatives—without giving her a chance to rebel, as he once did. “I won’t tell her what to do. I simply suggest what’s best for her, and then let her make up her own mind,” he insists.

For instance, she used to date quite a wise guy, at least in Troy’s eyes. He was particularly upset when Eve told him that he always carried a bottle in his car, and tried to talk her into taking a drink. “Had I forbidden Eve to see him, she might have done it behind my back,” he reasoned. “So we just had a heart-to-heart talk. I emphasized the trouble she could get into with this boy, then left the decision up to her. She stopped seeing him.”

Whereas at one time Troy would leave the house under almost any pretense, he now makes a point of getting together with his family several times a week—and likes it.

Looking back at the last few years, Troy still feels that his abrupt decision to leave home was best for all concerned. It helped establish his independence—and made a man out of him.

He feels constant compromises and halfway measures lead to nothing but trouble in any relationship—which is also the reason he had earned both the good and bad reputation with women!

Nan Morris was by no means his first love. When he was nineteen, he got engaged to a beautiful New York model. But as she grew more successful, Troy’s meager earnings couldn’t provide her with her constantly more expensive tastes, till the gulf between them grew to a point where it split them apart. “I saw it coming for a long time, yet didn’t have the courage to admit it to myself. Luckily one evening she made it quite clear what was happening. Although I was hurt at the time, it was best for both of us to recognize realities. It would have been much harder on both of us if I’d played the hurt lover indefinitely!”

His next infatuation was for a girl under contract to Universal-International, the same time he was tied to the studio. Her success came about much faster than his, and the New York episode repeated itself almost verbatim when she told him quite frankly one day that they weren’t right for one another any longer.

Again Troy preferred the abruptnness that wrote ‘finis’ to their romance to a long, dragged out affair. This is, he told himself, how he would finish a relationship if he were ever caught on the other end of the line—which is exactly what happened with Nan Morris.

Although they were not officially engaged, they had gone steady for two years. When Troy became interested in another girl, he tried to tell Nan as gently as possible. She refused to believe it.

The way it looked!

One evening, not long ago, he took out this other girl. But he was so tired after a long day at the studio that he asked if she minded driving herself home in his car, after dropping him off at his house. She didn’t mind.

The next day was Sunday. When she returned Troy’s Porsche, she arrived just as he got ready to leave to meet his mother and sister for church.

She too was tired from the night before, and asked if she could rest on his couch till he came back. He didn’t object.

Troy returned two hours later. He was just taking off his coat and loosening his tie when Nan arrived unexpectedly, says Troy. Through a peephole in his door, she could see a girl lying on the couch, covered by Troy’s bathrobe, and Troy taking off his jacket and loosening his tie. “She put two and two together, and made twenty-five out of it,” Troy said.

Nan frantically knocked on the door. The other girl hastily put on her coat, and ran out of the apartment, right past her.

Nan started to yell. When she kept it up, Troy took her inside and shook her hard by the shoulders, till she stopped. When she refused to believe what he told her, he angrily asked her to leave, insisting it was all over between them!

While this seemed abrupt and ungentlemanly to Nan, under the circumstances Troy felt it was the only sensible thing to do. Apparently he was right, for two weeks later Nan called uneasily, and asked to see him. He agreed, though still fearful of another scene. Instead she wanted his advice on a professional matter.

Several weeks have passed since then, Today, Nan and Troy still get together occasionally. They are no longer a romantic item. But they have managed to re-establish a friendly relationship in spite of what has happened, or maybe because of it. And even if Nan’s closest friends don’t understand, she does—and that’s what counts for Troy.

Still, he’s embarrassed about the incident. “This sort of thing never happened to me before, and I hope it never will again,” he insists. “I’d much rather be jilted by a girl than appear to be the one responsible for something like this.

So these are the two faces of Troy. So different, yet so inter-related that one could not be without the other. Whether one likes or dislikes him for what he is, whether one agrees or disagrees with the way he manages himself, and others, one has to admit there’s nothing wishy-washy about him.

Thank heavens—Hollywood has found a man again. A real man!

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1960

No Comments